September 21, 2021

The story goes like this.

A breeze blows. A door bangs open. A bear bursts in.

Not just any breeze — an ill wind.

Not just any door — the front door to a zombie’s house.

Not just any bear — a fierce mass of fur. A fiery mess of furry fury. In a snit. And dripping spit and spite.

The bear is angry. Hungry. Mad to munch some zombie cub.

He’s come hunting.

The bear snorts softly, shuffles down the hall, swivels his head from side to side. He wants to scare. To tear. To maul. To rip the pictures from the wall.

Needle-sharp hindclaws clickity-click on the floor. Needle-sharp foreclaws dig ker-rippppp the wallpaper.

The bear busts into the kitchen, and stops. Nose to the air. Sniff-sniff. Where’s the zombie cub? Sniff-sniff. His mouth pulls back in a black-lipped grimace. Spittle dripping from his lips. Some ancestral madness in his eyes. Wild night-stink wafting off wet fur. Breath-puffs steam the kitchen.

He circles the kitchen island. Patient. Sniff. A ripening zombie-smell. Click-click. Brute instinct takes over. He knocks a stool to the floor. Stands on hindlegs, peers into pots and pans hanging from hooks overhead. His thick skull knocks crockery. Metal utensils chime. He wheels around and a massive iron cookpot wobbles off its hook and crashes to the floor.

The bear’s rage rises. He abandons all caution now. Cares nothing for noise. Where is that cub? Where? Muddy pawprints tattoo the kitchen floor. He rips cupboard doors from hinges. Tears drawers from counters. Sprays silverware everywhere.

He hears the sound.

A soft wet cry.

Something waking from the sleep of the undead.

The bear scowls, glowers, growls. Where is it?

Behind the stove. He pads over, peers behind.

Oh you sweet zombie flesh.

He reaches out an arm.

He hears a gasp.

He turns.

A zombie woman gapes at him. She holds a candle in her hand. Her eyes are wide with terror.

The bear charges toward her and stops. His bulk seems to fill the kitchen. His eyes narrow. Paws flex. He gathers himself for a mighty, house-ripping, earth-shaking, bone-breaking roar.

The woman wavers.

The world waits.

“Um … roar?” the bear warbles weakly.

“Cut, cut, cut!” shouts a voice. “Stop the scene. Darling, you need to find your roar.”

The Bear was No Bear

The Bear was No Bear“Ah, fungus!” yelled the bear. “Mucus, rot, and pusballs! Phlegm and goo!”

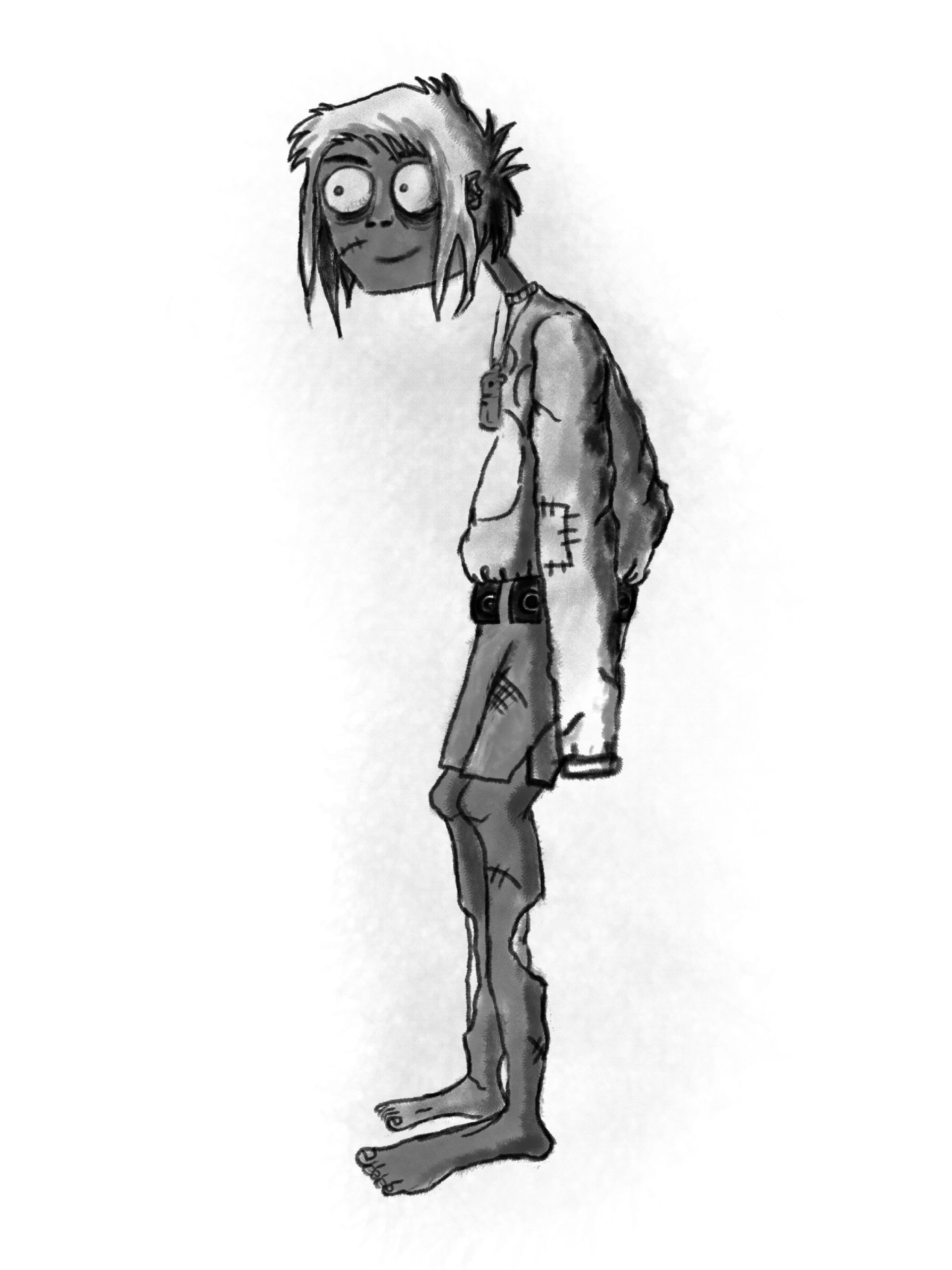

This bear was no bear. Nor no he. He was a she, and she was Moldylocks — Moldylocks LaMort. Just past her 12th unearthday, Moldy was an undersized zombie girl with different-sized feet currently wearing a bear costume stomping around the stage of the Zombie International Theater Company. The ZITCO: a house in the front, a theater in the back, and a mix of everything inside.

The woman calling for more roar was her mom, Dorothy.

Moldylocks clonked toward the back of the stage, around the backdrop painted to look like a kitchen, and into the house.

She banged the counter of the kitchen island, the real kitchen island, and she roared, “RAWRRRR!”

“Not bad, not bad at all,” said Dorothy, shambling in behind her.

“It’s easier to roar when I’m inside,” said Moldylocks.

“You just need to bring your inside roar outside,” said her mother.

The biggest event on Plainfield’s theatrical calendar every year was the ZITCO’s performance of Grizzly Hair, a musical about menacing bears. The lead role always went to a 7th-grader from Plainfield Middle School, and this year, Moldylocks was one of the five candidates chosen to audition.

To ensure the lead actor could stand up to the rigors of live theater, the audition was a grueling test. Taking place on a single night, it consisted of four demonstrations of bear-ness: honey-guzzling, wrestling, a roar-off, and a dramatic monologue.

Each event was scored by a panel of three judges, and the whole town always came to watch the five nervous zombie adolescents struggle, soar, and sometimes, fall flat on their faces.

Legends were born. Reputations were made. Limbs were lost.

The audition was nearly as popular as the musical that followed a month after.

Some who auditioned, like Jeminy Stinkpit, did so because winning meant a scholarship to the summer theater camp at Rotburg State University.

For Moldylocks, who only had one friend, winning was a ticket out of Loser City.

Moldylocks could really have used the help of that friend, Scarlet “Scar” Bone, but Scar was gone for a week, tagging along on her dad’s business trip to Rotburg.

If she was going to find her roar, she was going to have to do it on her own.

And the audition was in a week.

Dorothy lurched to her daughter, pulled her close, and buried her face in her daughter’s green hair, inhaling the smell of rotted moss.

Moldylocks sagged into her mother’s embrace. “I’ll never make it,” she said.

“Look at me,” said Dorothy.

Moldylocks looked into her mother’s beautiful face. Dark circles under the eyes. Thin, blackened lips. Careworn lines on her cheeks. A touch of greenrot. Long, irregular hanks of green hair, like her daughter’s. It was a face that radiated love and trust.

“I’ve got good news and I’ve got other good news,” said Dorothy. “Which do you want to hear?”

“The other good news,” said Moldylocks.

“The other good news is that we’ve got a week.”

“What’s the good news?”

“Step out of that bear suit first,” said Dorothy.

Moldylocks did as she was told. The bear suit became puddled fur at her mismatched feet.

“Now, come.” Dorothy steered her daughter to the tall floor mirror by the bottom of the stairs.

Moldylocks took in her reflection. Before her stood a zombie girl wearing a hand-carved bear-totem necklace, a faded sweatshirt with the hand-painted bloody bear-paw-print on the front, and a leather belt with bears carved all around it. She had a bear bandana hanging out the back pocket of her cutoff jean shorts. Her hair was short, like green fur. And even her dirty face had a brownish tinge to it.

“The good news,” said Dorothy, “is that you are now, and have ever been, Plainfield’s one and only Bear Girl. You’ve got more bear in you than anyone ever did. You just have to …”

“I know, I know. Bring the inside outside. But how, Mom? You know how I freeze up in front of people.”

Dorothy looked outside. Late spring shadows were inking the woods surrounding the ZITCO. “There’s a little light left in the day. Go practice in the woods till I call you in for dinner.”

Moldylocks nodded.

“And bring Mr. B. F. Doolittle.”

“Why?”

“Sweetie, you’ve had him since the day you were unearthed. He’ll remind you of your bearness. Keep him with you this week. Now, hurry, it’s going to be dark soon.”

Moldylocks grabbed her bear costume.

“Remember,” said Dorothy, “see the bear, be the bear!”

That reminded Moldylocks of something. “Mom,” she said, “do you know where the bee blaster is? I have the presentation Monday.”

“I’ll look for it. Now go, go.”

Moldylocks lurched outside, which was the only way to get upstairs.

The ZITCO had long ago stopped being a conventional house. It was, in fact, so crowded with theater gear that the inside stairway was unusable. Moldylocks clambered up the fire escape, scooted through the top-floor window, and hurried down the hall to the room she’d shared with her mother since the day she was unearthed. Sometimes Moldylocks wondered what it would be like to have a dad around. Her new friend, Scar, did — and he made the best brainwaffles Moldylocks had ever tasted. Instead, Moldylocks had a fiercely independent mom who’d always wanted a child, but didn’t want to bother with having a man zombie around. “One child is enough,” she liked to joke.

But Moldylocks never entertained the dad daydream for long. Her undeath was full. She had her mom, the theater, and her beloved stuffed bear, Mr. B. F. Doolittle. He was friendly. He was ugly. He was her fugly bear. She grabbed him off the dirtbox bed, climbed back down the fire escape, and lurched into the woods.

The boggy backwater clearing known as O’Putrid’s Pond was Moldylocks’s happy place. Happy because no one ever ventured back there. No one who could tease her. No one to ask why her bedroom wasn’t in the basement, like a normal zombie kid. No one to criticize her bear gear. No one to call her a loser.

She sat Mr. B. F. Doolittle on a boulder, walked a few paces back, and faced him. She cleared her throat and began to chant.

“I’m a bear down to my core.

Give me honey and I want more.

I wrestle zombies, it’s a war!

When I say ruh, you say oar! Ruh. … ”

She cupped a hand behind her ear.

Mr. B. F. Doolittle said nothing.

“Ruh … ” she waited.

“… oar,” she whisper-shouted in answer to herself. “Now that’s what I’m talking about!”

Moldylocks scanned the tops of the trees, dense moldfirs and deadwoods.

She tried a roar. It floated out over the pond and dropped quietly in the water.

Again. The roar went a little farther, but not by much. Her last roar dropped into the mud at her feet.

“I’m such a goo-head, B. I can’t roar. I can’t eat honey. And wrestle? Look at me! I’m the scrawniest bear ever. Bear Girl. Riiiiight.”

Moldylocks sat down on the boulder next to her fugly and thought a while.

“I don’t get it. What am I missing? All I ever wanted was to be a bear. To be dangerous, dumb, and angry.” She sighed. “Bears are soooo cool.”

Moldylocks leaned back on the boulder and closed her eyes.

“How do you do it, B?”

Moldylocks sat up, and stared hard at her fugly. “I’d do anything to be a bear. Anything.”

Time to go home. Dark was coming.

While Moldylocks played bear, Dorothy did battle — against the ZITCO. The theater seemed to have a mind of its own. Sometimes, on cold winter nights, when the cold poured in through the thin soil of her dirtbox bed, when she could hear the old house creaking and groaning, Dorothy did wonder if the house was alive (like the wild animals that roamed the Plainfield Woods) or perhaps undead —just another restless member of the family. And how could a house collect so much stuff? The ZITCO was bursting with theater props.

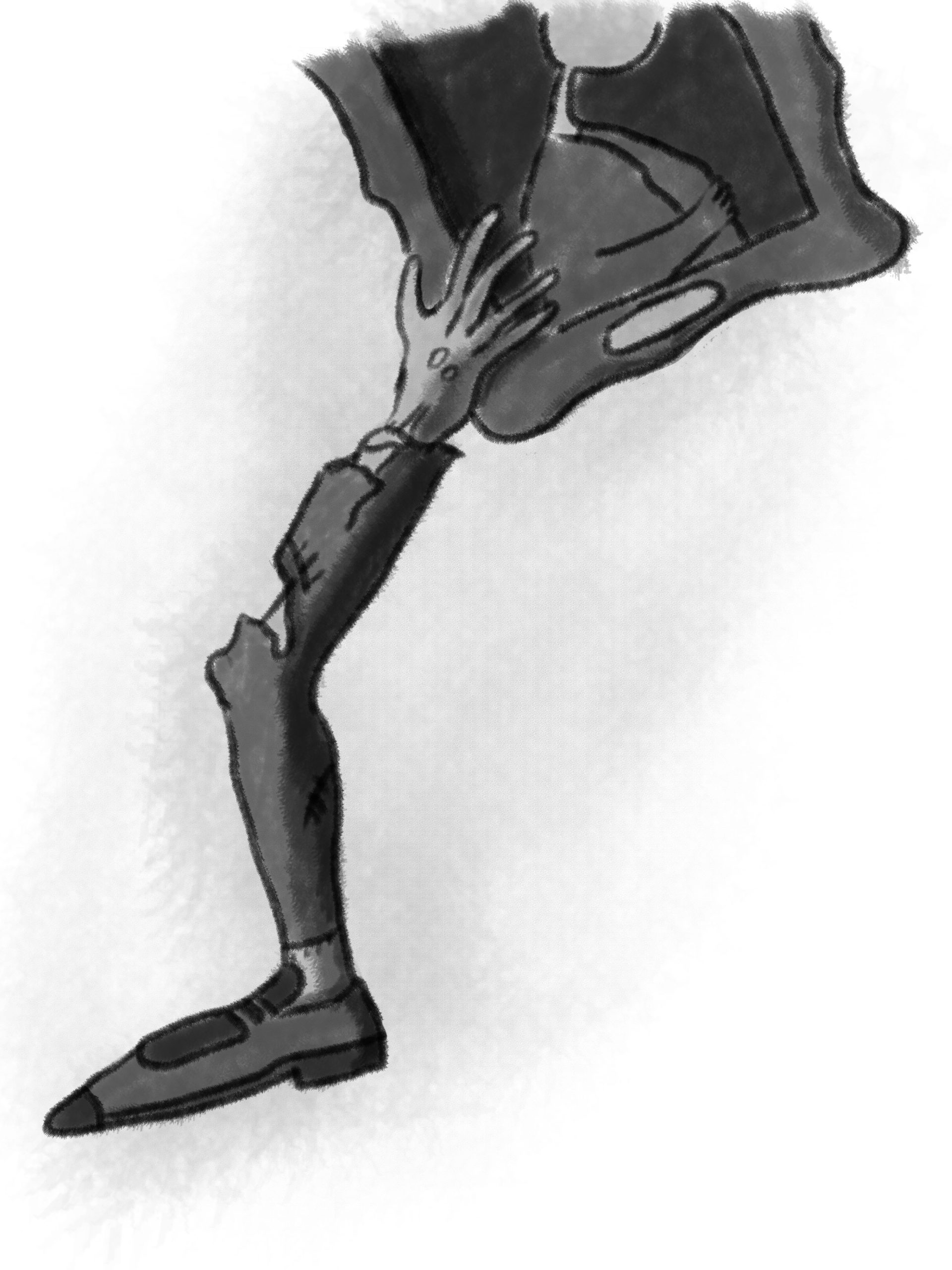

She and her assistants were always pushing back against the forces of disorder. Santiago Mano, her stagehand, and Harry Halfleg, her stageleg, now worked to put the stage back together after Moldylocks’s rampage. They patched wallpaper, straightened pictures, closed cabinet doors, and set the cookpot back on its hook. It was slow going.

Harry, merely a leg, and Santiago, just a hand, could only work so fast.

Despite their limitations, they were good assistants. Hardworking and loyal — as long as Dorothy didn’t accidentally call Harry a stagehand or ask Santiago to toe the line.

Santiago climbed to his perch atop Harry’s crusty femur stub. Once in place, he tapped Harry twice with his index finger. Harry hopped to a spot under a tilted picture and began to bounce up and down. At the top of Harry’s hops, Santiago would stretch out a finger to try to straighten the picture. Instead, he knocked it off the wall. The picture fell with a crash to the stage. When Harry felt the glass sprinkle his toes, he and Santiago rode off to the supply closet to fetch a broom and a dustpan. It took two trips. Santiago could only carry one thing at a time.

So went days at the ZITCO.

“Keep up the good work, guys,” said Dorothy.

Chaos and disorder were always part of the theater, but this past season had been especially trying. As always, Dorothy had put on tried-and-true shows — the crowd-pleasers that Plainfielders knew and loved. But, also as always, she tried to put her own spin on the classics.

In “The Sound of Mucus,” Dorothy had rewritten the ending so that the Von Trapp family feasts on Nazi guts instead of fleeing over the mountains. Dorothy also altered “West Side Gory” so that the lovebirds did not decompose at the end but instead ate the brains of both of the rival gangs. Then there was “The Gizzard of Oz,” which had Gorothy stay in Oz after dining on the old wizard’s gizzard.

Her genius was lost on the people of Plainfield, however, and each show lost more money than the one before it. Dorothy fell farther behind on her rent. “I just wanted strong female leads,” Dorothy had said to Conniption Stinkpit, her landlord, after each show.

Dorothy shook herself out of her daydreaming. “Oh, what’s wrong with me?” Harry and Santiago paused their sweeping. “Why can’t I just tell the story plain?” They, of course, had no answer, so they simply twitched sympathetically and got back to the task at hand. And at leg.

Dorothy once again found herself grateful that they worked for free. Almost for free. Santiago worked for knuckle-crackings; Harry was fond of foot rubs.

“When you’re done sweeping,” Dorothy called, “can you two hop out and check the mail?”

Santiago gave her a thumb-up.

Dorothy climbed the fire escape to the second floor and lurched to the upstairs prop room, hunting for the bee blaster and any Grizzly Hair props she could find. She took a deep breath and opened the door.

The room was a forest of props, stuffed floor-to-ceiling with …

… marquees and skeleton keys … mannequins and sequins … bolts of fabric and bags of fasteners and bursting bins of phony fingers … carpets and capes; puppets and drapes … garden rakes and magic beans and foaming flakes for snowfall scenes … worn canteens and jars of brains; old magazines and rusty chains … teacups, chairs; artificial buttercups, and spares … bathing caps and ancient maps and one machine for making claps … clocks and cloaks … headdresses and party dresses … feather boas and feather pillows … axes, maces, and swords; a broken sign that said “Dread undead who tread the boards” … cans of skin spackle … caddies of gut putty … paints and brushes; pants and bushes … the cardboard disc of a full summer moon; an old guitar, which was dramatically out of tune … masks and costumes for bears and zombies; plus all kinds of gear for minding bees.

Dorothy waded against the surge, occasionally plucking an object from a pile, keeping this, setting that back down. She fought her way to the back of the room, and shoved aside a pile of styrofoam coffins. Then she saw it. The bee blaster. It looked innocent enough, like a watering can wearing a cone hat, but it was the key prop in the play and the universal symbol of how bears would destroy anything to get what they wanted. It was pure, distilled bear badness. Bad bearness.

This may help Moldy find her roar, she thought.

There came a thumping down the hall. Harry hopped into the doorway of the prop room and stopped, with Santiago still riding atop.

The hand held a fistful of letters.

“Coming …” said Dorothy, wading out to meet them. She took the letters and stuffed them in a frock pocket without opening them. “Let’s head downstairs, fellas. I need some fortification before I open these.”

After she’d brewed a pot of coffee, Dorothy eased herself onto the sagging leather sofa. She allowed herself a fleeting moment of rest, if not complete relaxation, and inhaled the smell of baking brain stroganoff. Dorothy took a sip of Wakeful Dead coffee and turned her attention to the pile of letters. An overdue notice from Plainfield Sewage. A bill from Plainfield Water Co. An invitation to the annual limb-roundup pre-party. A summer-school catalogue from Rotburg State. And a letter from C. Stinkpit.

She tapped the letter on her knee, hesitating.

“Best get it over with,” she said to her assistants, nestled beside her on the sofa. Dorothy drained her coffee in one last, fast gulp and ripped open the letter.

My Dearest Dorothy,

It is in the spirit of our long friendship that I write to you. We know each other well, so I trust you will appreciate my candor in this communication. Time is of the essence, and regrettably overrides the pleasantries a personal visit would afford.

I’ll proceed directly to the point.

As you are aware, your last five productions have lost money.

As you are aware, the date of the “Grizzly Hair” audition fast approaches.

As you are aware …

… it is the showpiece event of the season and an annual tradition;

… it is the story that shows the zombie place at the top of the natural order of things;

… the lead role can make a career;

… it is my daughter’s abiding dream and sincerest desire to win the role.

I feel compelled to share with you our excitement and affirm that I look forward to a spirited week of respectful competition. As you know, next Friday night, you, my dear friend Tom Head, and I will make our final judges’ decisions and crown a victor.

My fervent hope is that no matter what the result may be, you and I shall afterward share a cup of tea as friends, even though one of our daughters will most certainly be heartbroken.

Here the twin themes of my letter intertwine.

I have given up expectation of receiving the year of back rent you owe me and which, when we last met, you promised you would forthwith furnish.

Still, I maintain hope of remuneration. If, however, that is but a fool’s dream, please do not hesitate to suggest alternate accommodation, any such as you can imagine. I am all ears.

We are women of daring!

And there are so very many ways to repay a debt.

Most Affectionately Yours,

Conniption Stinkpit

Dorothy smacked the sofa cushion so hard she bounced Harry and Santiago to the floor. “Sorry guys!” She scooped them up and repositioned them. “I can’t believe she’s suggesting what she’s suggesting.”

Harry waggled his toes. Santiago made a fist.

“She wants to bribe me.”

“Who does?” asked Moldylocks, who had just come in from the woods.

“Oh, it’s nothing, really. Just that some people will do anything to be actors. How’s your roar?”

“I still can’t find it.”

The Festerings neighborhood was the grandest in all of Plainfield, full of coldly elegant homes all rank, dank, and gated to guard their secret dark interiors. Roofs were a thicket of gables and turrets. Basement bedrooms dripped spiders onto thickly soiled dirtboxes. Upper stories oozed lush decay along their reeking parlors, powder rooms, and servants’ quarters.

Deep into Friday evening, a thin light flickered in a second-floor room of the grandest house of them all, creating a two-zombie shadow drama on the wall. One shadow stood, hands behind its back. The other shadow lay on its stomach — pushing up, down, up, down.

“95, 96,” counted the standing shadow.

Grunts from the low shadow.

“97, 98 … two more,” barked the standing shadow.

The low shadow shook. “99,” it panted. “99 ½,” arms quivering. “100.” The shadow staggered to its feet.

“Form: Horrible,” hissed the larger shadow, making notes on a clipboard. “Endurance: Awful. Attitude: Terrible.”

“Yes, mother,” said the smaller shadow, still panting from her effort.

“What are you?” asked the woman.

“A bear,” said the girl.

“Louder. What are you?” asked the mother.

“A bear!” said the daughter.

“Like you mean it,” shouted Conniption Stinkpit.

“I AM A BEAR!” screamed Jeminy Stinkpit.

Conniption put her face close to her daughter’s. Their splotchy gray noses touched. One pair of bloodshot yellow eyes stared into another. “Not yet, you aren’t. You’re still just a zombie girl. Now, to the honey.”

Conniption pointed to the table by the wall. A jar of honey waited. Jeminy grimaced and followed her mother.

“Remember, bears are about power,” Conniption explained. “You need to dominate the honey.” Conniption spooned a small glob into her daughter’s mouth. Jeminy choked it down and adjusted the feather boa around her neck.

“Bah! Your honey score is 1! Again.” Another swallow of honey and a tug at the boa.

“Leave the boa alone,” Conniption barked. “You don’t want to draw attention to it during the competition. Now take another spoonful of honey. You must build up a tolerance.”

Jeminy nodded. Her mother’s training plan called for 10 spoonfuls of honey tonight, and she had eight more to go. Gulp by gulp, she choked the honey down.

When she’d finished, Conniption wasted no time. “Now let’s get right to the wrestling. Remember — in the audition, the transition from event to event will be quick.” Conniption snapped her fingers. “Like that!” She stomped the floor twice. “Arnold!”

Out of the shadows stepped a giant with veiny arms, muscled legs, and patches of thick black hair covering his back. He was a fearsome wrestling competitor, made more intimidating by his brown spandex wrestler’s unitard with a yellow S across the chest. Jeminy’s only advantage was that he wouldn’t be able to see or hear or smell her.

Arnold had no head.

Jeminy crouched. Arnold, sensing her movement, turned toward her. The two circled, bobbing and feinting. Arnold flicked his hands out, trying to locate Jeminy. Jeminy grabbed for Arnold’s wrist. Arnold brushed her arm away. Jeminy dashed behind him and went for a half-nelson. Arnold flung her aside. Jeminy moved back in front of Arnold and dove in for a takedown. It was like trying to take down a tree. Arnold caught her, flipped her over, and quickly pinned her.

“Thank you, Arnold,” said Conniption, stomping the floor again. “Well done. Back to the attic, now. Thank you.”

Arnold shuffled off, hands groping in front of him. Conniption narrowed her eyes as Jeminy struggled to her feet. “Pathetic,” she said to her daughter. “Your wrestling score is 0! Let me hear your roar.”

Jeminy’s throat was raw from the honey and she was tired from wrestling. When she tried to roar, all that came out was a raspy whisper.

“Negative 10!” yelled Conniption. “How do you ever expect to win?”

“I don’t know, Mom.”

“Obviously.”

“I’ll work harder.”

There was a thump near the doorway. Arnold had walked into a wall. Conniption stomped the floor. Stomp … stomp-stomp. Arnold waved, moved to his left, and headed out into the hall.

Conniption turned back to her daughter. “I don’t want you to just win. I want you to annihilate the competition — especially the LaMort girl.” Conniption Stinkpit tapped her pencil thoughtfully on the clipboard. “That’s it. I’ve decided! You’re going TBI for the rest of the week.”

“TBI?”

“Total Bear Immersion.”

Meanwhile, on the outskirts of town, in the upstairs bedroom of a homely house, another mother-daughter scene was unfolding.

Two shadows appeared upon the wall. One sat on the dirtbox bedframe beside the other, who was settling in to sleep.

These shadows were still.

Dorothy brushed the dust off Moldylocks’s dirtmask and smoothed the dirt of the bed around her. The soil was coarse. It didn’t clump like the moist dirt in the finer dirtboxes of the nicer houses. Sometimes Moldylocks would wake up shivering. When she did, she’d climb into her mother’s dirtbox, where the two of them would cuddle, snug as skinbugs, dreaming dreams of bears and theater.

“I need to get us some better dirt,” she said to her daughter.

“But then we wouldn’t snuggle as much,” yawned Moldylocks.

Moldylocks clutched Mr. B. F. Doolittle to her chest and touched her bear-totem necklace. “Mom, do you think I have a chance?”

Dorothy patted her hand. “I think you have a very good chance.”

“Even though Jeminy’s mom’s a judge?”

“Remember, Tom Head is the other judge, and he’s honorable. Besides, don’t even worry about the judges. Just focus on finding your roar. If you find it, you’ll be just fine, Bear Girl.”

Moldylocks frowned. “Mom, sometimes I’m not sure what that means.”

“Good thing you have a week to find out.”

“That’s not very long.”

“It is if you Go Full Bear,” said Dorothy. “So, starting tomorrow, I want you to do everything the bear way.”

“Everything?” asked Moldylocks.

“All the way,” said Dorothy.